Tears welled in my eyes as I sat in the 16th Street Baptist Church watching a video about the 1963 killing of four young black girls when a bomb planted there by Ku Klux Klan members exploded. In the darkened room, I heard a couple of other sniffles around me. My sleeve became my Kleenex. And when the lights came back on, I quickly wiped my eyes, although my heart still felt tight and numb.

When I arrived in Birmingham two days earlier, I was ready for a deeper education about the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. As one of the most racially divided cities in the United States, Birmingham had become the center for much of the struggle, with Martin Luther King Jr. spending time in jail there, and the Freedom Riders in 1961 being beaten badly and their bus burned.

At that time, I was such a young white girl from California that the struggle for equality seemed distant, not a part of my life, and not part of my childhood reality. So, decades later, here I sat in the 16th Street church, feeling the hot tears welling in my eyes and tracing a path down my cheeks. I didn’t realize this exploration of civil rights would grip my heart this hard.

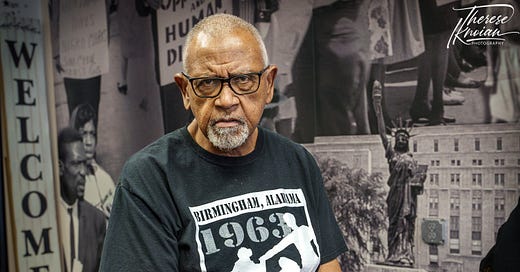

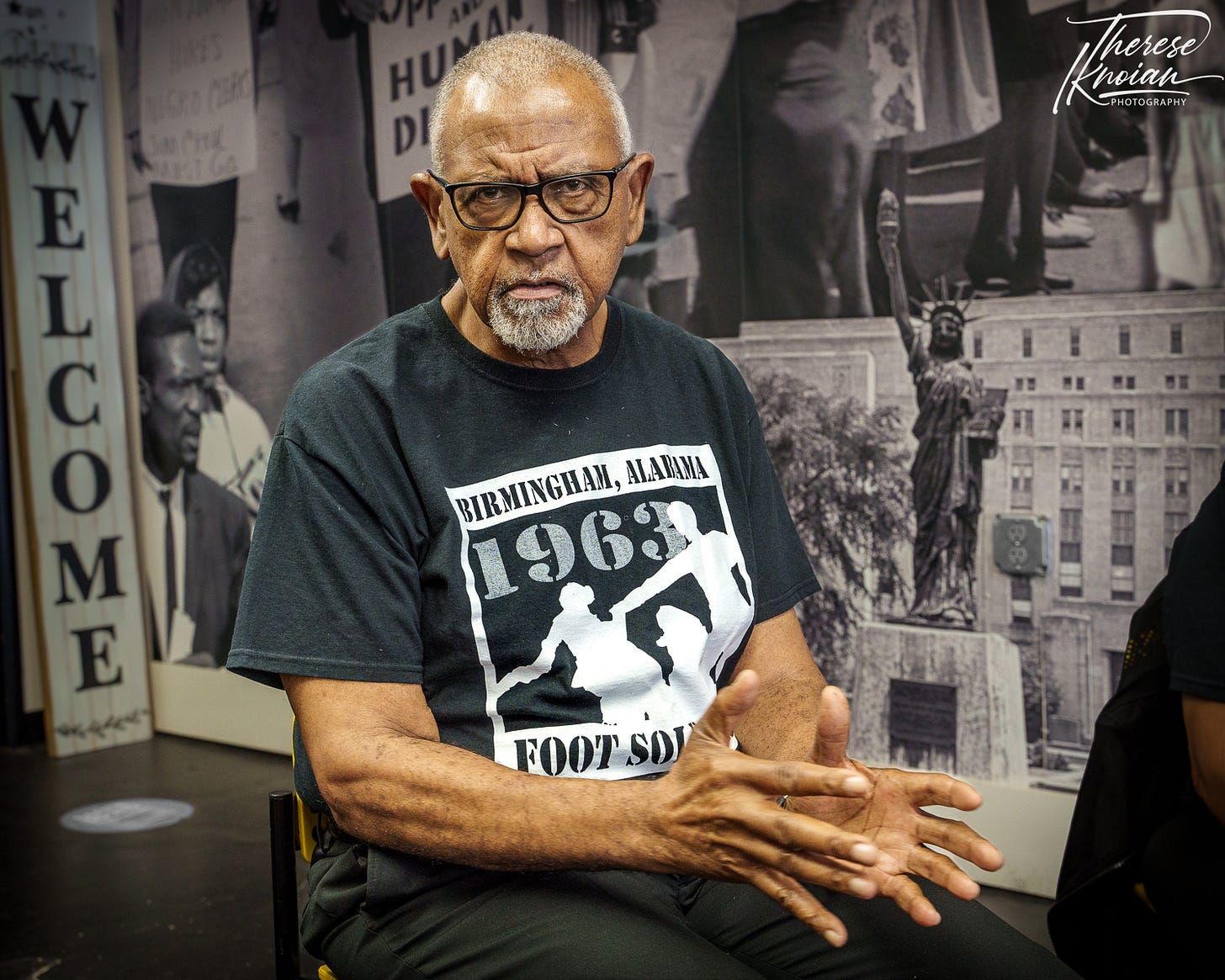

Later, Barry McNealy, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute's historic content expert, told me that seeing people in tears in the institute’s halls was not unusual. As he put it, the experience is “transformative.”

I experienced that emotion swell in the 16th Street Church. After the video, I walked around the side of the church where the hall where the girls were getting ready for Sunday School that fateful day had once stood. A low-profile black marble plaque (pictured above) sits on the ground, with writing small and thin enough that you could easily blow past it. I stood and stared at it, trying to imagine a place so angry that people would bomb a Sunday School. The bomb had been so strong that it was felt across the city.

“Bomb-ingham” is what the city was called by some back then, Terry Collins told me the next day. Collins, now 76, was one of the so-called Children’s Crusaders. One of hundreds of children and teens who marched and demonstrated peacefully – often because the adults in their lives would lose jobs if they took to the streets.

During my visit, I sat for several hours talking with four of the Children’s Crusaders, all of whom participated in some way in the struggle for equality and civil rights. On days when the secret call would go out with the song lyrics, “Googly Woogly,” the kids would turn up en masse, filling the streets, Collins said. The police would use water cannons against them with a stream so strong that it would blow them down the street, tear off their clothes, and make their skin feel as if it were on fire. They remained peaceful, but that didn’t mean being compliant.

“Silence is acquiescence,” said Danny Ransom, 73. “Complacency is acquiescence. Doing nothing is not the answer.”

So they did something, and it bubbled up six decades ago into an anger-stoked but peaceful revolution. “We had to turn a cheek when we marched,” said Paulette Roby, 75, “but they bombed the church?!?!? They went too far. We were angry.”

I listened to these crusaders talk about snarling police dogs, painful experiences of being blasted by water from high-pressure cannons, beatings from police batons … while they walked or sat and did not react. Could I have done that? I did a lot of listening and contemplating during my time with these four courageous souls in the office of the Civil Rights Activist Committee. The committee was formed in 1991 to recognize the role of the “foot soldiers,” such as the Children’s Crusaders, to document their stories and to continue the fight for equality.

I am mesmerized by their eyes as they recall those times decades ago, and I can see the fire and passion that still live within them. They all continue to be active in the ongoing fight for human rights, speaking out, giving interviews, and striving to pass on the motivation to keep breaking down barriers.

“Fight for the change you want to see,” Nadine Smith, 74, said. “You have to continue to fight for your rights.”

Despite living a relatively sanitized life far from these struggles, I found out after high school that even my immigrant grandparents and parents had faced discrimination: Armenians weren’t even allowed to join certain clubs until into the ‘70s and ‘80s. Lack of civil rights existed everywhere … and still does.

My experience in Birmingham was transformative. I was particularly left in awe of the courage of the Children’s Crusaders. And I was left hoping that if needed, I, too, would find I have the same courage.

— Story by Therese Iknoian - See more photos by Therese Iknoian here – all available for purchase for gifts or just for you!

Ugh. Yes. I have cried those tears, listened to the elders who were young then. Oh, that we all could have such courage. Thanks for articulating this.

It is quite sad that even children had to be strong and stand up against the injustice. Parents always try to shield their children from all the bad things. They realized though that everyone was needed on board.

I think now is that time again. I agree to stay silent is to acquiesce.